The space telescope’s powerful infrared gaze provides a new view of how the galaxy has changed over billions of years.

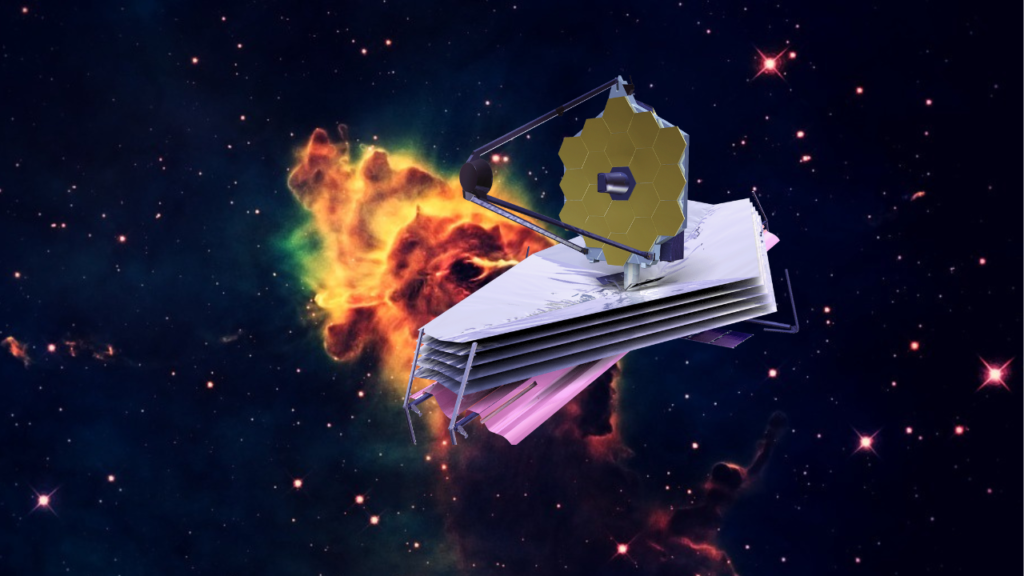

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has peered into the chaos of the Cartwheel Galaxy, revealing new details about star formation and the galaxy’s central black hole. Webb’s powerful infrared gaze produced this detailed image of the Cartwheel and two smaller companion galaxies against a backdrop of many other galaxies. This image provides a new view of how the Cartwheel Galaxy has changed over billions of years.

The Cartwheel Galaxy, located about 500 million light-years away in the Sculptor constellation, is a rare sight. Its appearance, much like that of the wheel of a wagon, is the result of an intense event – a high-speed collision between a large spiral galaxy and a smaller galaxy not visible in this image. Collisions of galactic proportions cause a cascade of different, smaller events between the galaxies involved; the Cartwheel is no exception.

The collision most notably affected the galaxy’s shape and structure. The Cartwheel Galaxy sports two rings – a bright inner ring and a surrounding, colorful ring. These two rings expand outwards from the center of the collision, like ripples in a pond after a stone is tossed into it. Because of these distinctive features, astronomers call this a “ring galaxy,” a structure less common than spiral galaxies like our Milky Way.

The bright core contains a tremendous amount of hot dust with the brightest areas being the home to gigantic young star clusters. On the other hand, the outer ring, which has expanded for about 440 million years, is dominated by star formation and supernovas. As this ring expands, it plows into surrounding gas and triggers star formation.

Other telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope, have previously examined the Cartwheel. But the dramatic galaxy has been shrouded in mystery – perhaps literally, given the amount of dust that obscures the view. Webb, with its ability to detect infrared light, now uncovers new insights into the nature of the Cartwheel.

The Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), Webb’s primary imager, looks in the near-infrared range from 0.6 to 5 microns, seeing crucial wavelengths of light that can reveal even more stars than observed in visible light. This is because young stars, many of which are forming in the outer ring, are less obscured by the presence of dust when observed in infrared light. In this image, NIRCam data is colored blue, orange, and yellow. The galaxy displays many individual blue dots, which are individual stars or pockets of star formation. NIRCam also reveals the difference between the smooth distribution or shape of the older star populations and dense dust in the core compared to the clumpy shapes associated with the younger star populations outside of it.

Learning finer details about the dust that inhabits the galaxy, however, requires Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). MIRI data is colored red in this composite image. It reveals regions within the Cartwheel Galaxy rich in hydrocarbons and other chemical compounds, as well as silicate dust, like much of the dust on Earth. These regions form a series of spiraling spokes that essentially form the galaxy’s skeleton. These spokes are evident in previous Hubble observations released in 2018, but they become much more prominent in this Webb image.

Webb’s observations underscore that the Cartwheel is in a very transitory stage. The galaxy, which was presumably a normal spiral galaxy like the Milky Way before its collision, will continue to transform. While Webb gives us a snapshot of the current state of the Cartwheel, it also provides insight into what happened to this galaxy in the past and how it will evolve in the future.

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.