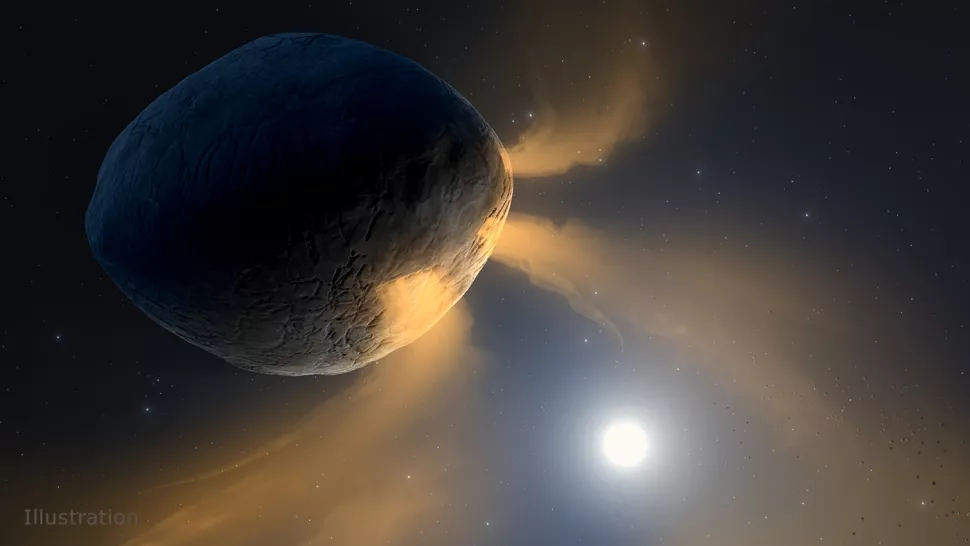

The asteroid Phaethon’s tail is not made of dust after all, scientists have discovered.

Astronomers observing the strange “rock comet” hybrid Phaethon as it passed the sun have found a surprise that could upend 14 years of thinking about the weird asteroid.

The asteroid Phaethon, which gives us the Geminid meteor shower every year and was discovered in 1983, has a strange brightening from what appears to be a tail of sodium atoms, and not dust as previously thought, the researchers found.

“Our analysis shows that Phaethon’s comet-like activity cannot be explained by any kind of dust,” said Qicheng Zhang, a California Institute of Technology PhD student who led the new study into Phaethon, in a NASA statement (opens in new tab).

Scientists made the discovery while recording a two-hour sequence of Phaethon on May 15, 2022, using the comet-hunting Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). At the time, the 3.6-mile-wide (5.8 kilometers) asteroid was making its closest approach to the sun, coming within 13 million miles (21 million kilometers) of the star.

As Phaethon made its close approach, or perihelion, radiation from the sun caused the space rock to vent material. This dust could be seen as a bright cloud surrounding the asteroid by SOHO’s sodium-sensitive orange filter. Though a tail trailing Phaethon made of the same ejected material is less obvious, it is visible when images collected by the various filters of SOHO are stacked together to create a single image.

The venting of dust and gas in this way to grow tails and halos, called comas, is common to comets and is the result of solid ice being transformed into gas and blowing off material. This creates clouds of cometary dust around the sun that enter the Earth’s atmosphere at high speeds when our planet passes through them causing meteor showers. The venting of material from comets also causes a sudden brightening of these icy bodies as they approach the sun.

Since 2009 scientists have been aware that Phaethon, despite resembling an asteroid, not a typical comet, does the same thing. Also, during its perihelion, Phaethon grows a cometary tail hundreds of miles long and facing away from the sun.

Scientists previously thought that this comet-like behavior of Phaethon was caused by the release of small dust grains from the cracking of the asteroid’s surface as it passes the sun and this led to Phaethon being dubbed a “rock comet.”

The new SOHO observations taken with its Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) telescope reveal these comet-like factors may instead be caused by the emission of sodium atoms which are excited by the sun and glow orange, similar to a street lamp, a phenomenon called “fluorescence.”

“Our unique observing plan found the mysterious asteroid Phaethon for the first time in SOHO data,” Zhang said in an ESA statement (opens in new tab). “The distinctive filters of the 27-year-old LASCO camera were used in a special interruption to the regular observing schedule to uncover these hidden secrets.”

The team followed up their observations by digging through a veritable treasure chest of SOHO data showing that Phaethon, which has an orbit of just 524 days, is visible in LASCO images from 18 different orbits dating back to 1997. The researchers also used archival imagery from NASA’s STEREO sun-watching mission for similar Phaethon orbits.

Unraveling the origins of the Geminids

The findings help shed light on the events that could have occurred to Phaethon to create the dust cloud that gives rise to the Geminds.

Though the sodium outflow detected isn’t powerful enough to lift dust particles, this discovery suggests an unobserved and unknown disruption of Phaethon, perhaps as long as two thousand years ago, could have created the debris that causes the Geminids.

The presence of a fresh and volatile sodium layer at the surface of Phaethon also suggests that another mass-loss event may have resurfaced the asteroid as recently as 1,000 years ago. Further study of Phaethon by SOHO could thus reveal the precise origin of the Geminids.

Phaethon isn’t the only object that emits sodium when it skirts the sun, the closest planet to the star Mercury also exhibits a bright sodium tail that peaks around two weeks after its own perihelion. The team used these sodium emissions from the tiny solar system planet to calibrate their observations of sodium from Phaethon. The sodium emission of Mercury is something that the BepiColombo mission, launched in 2018, will investigate once it is in orbit around the planet.

The findings made by the scientists could reopen the book on other objects that approach the sun which have been observed by SOHO. The brightening of some of these objects has led to them being classified as comets, but discovering the brightening of Phaethon opens up the possibility some of these objects may actually be asteroids as well.

“A lot of those other sunskirting ‘comets’ may also not be ‘comets’ in the usual, icy body sense, but may instead be rocky asteroids like Phaethon heated up by the Sun,” Zhang said in the NASA statement.

The Phaethon research is detailed in the April 25 edition of the Planetary Science Journal.