There was an electric moment on Feb. 22, when Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus lander, a rectangular prism built atop several slender metallic legs, touched down on the surface of the moon.

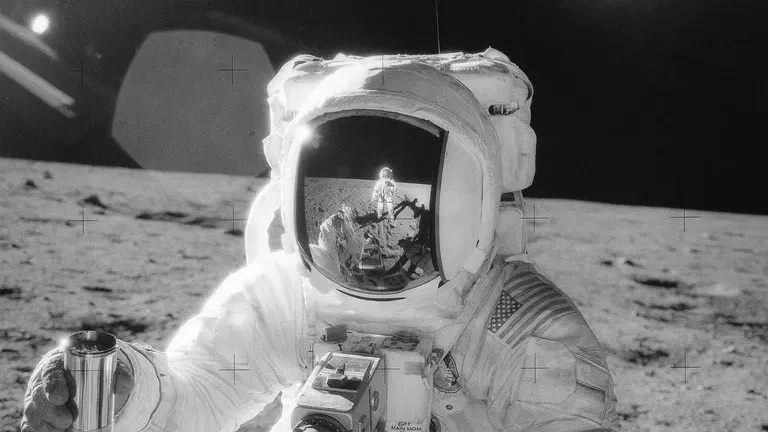

Surely, moon landings are always a thrill. The descent of Japan’s SLIM probe (complications and all) was inspiring, India’s Chandrayaan-3 mission rippled voltaic moments of its own, capturing the hearts of many across the world, and filmmakers are still making movies about the Apollo years. But there’s something special about Odysseus.

With this landing, Odysseus is officially the first private spacecraft to ever achieve the feat. It’s also the first American module to stand on the moon’s cratered body in over half a century. The last time a US-borne probe got to Earth’s reflective companion, it was 1972. And alongside these honors, Odysseus managed to carve out a very important place in humanity’s upcoming lunar odyssey — it proved that commercial lunar landings can work, and it suggests we’re about to see way more of them.

But while we’ve all surely caught the moon bug, lunar pioneers will soon need to contend with a pretty serious issue when it comes to space exploration.

“The thing about space is there is very little law,” Martin Elvis, an astrophysicist at the Harvard & Smithsonian’s Center for Astrophysics, said during this year’s American Astronomical Society meeting.

As Elvis says, the only firm type of space rulebook we have right now is the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which outlines tenets such as “states shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects” and “states shall avoid harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies.” But even that has its caveats.

“It’s not a prescription of laws,” Elvis said. “It’s a set of principles.”

Is space technically a free-for-all?

It should be noted that policymakers are indeed making strides toward laying out the ground rules as nations across the globe start racing to space with wide dreams of moon mining, lunar telescope building and even placing artistic marks on the lunar surface. You may also find it interesting that there apparently seems to be an aspiration of sending Bitcoin and NFTs to the moon as well.

The Artemis Accords, for one, is a US-led endeavor to get as many space-curious countries as possible to agree on peaceful exploration. It’s named for NASA’s ambitious Artemis program, which aims to get boots on the moon within the next couple of years — and on Mars someday, too. However, the Artemis Accords are also technically non-binding. Even if they provide a helpful framework for the day on which space laws are finally written, they’re not laws.

“If you pick up a rock and put it in a bag, it’s yours,” Elvis said of one Artemis Accords rule. “It belongs to the agency or the state that did that.”

This principle, to be fair, has already proven true to great degree as we’ve seen with the Apollo moon samples, Japan’s Hayabusa2 asteroid samples and most recently, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission asteroid samples. As Elvis puts it, “it’s a de facto thing.”

“The other change it introduces is to come up with the idea of safety zones around different installations,” he said. Though the astrophysicist admits he’s written a paper before about how this idea could be “terribly misused” to claim property on the moon, he emphasizes it’s a good idea in general. Still, what sticks out is the fact that none of this is written law.

“In terms of governance of the moon right now, there is none essentially,” Elvis said, though on the bright side, “there are ongoing approaches to develop laws for the moon.”

The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Space exists, for instance, an organization that meets rather often to discuss how to promote non-violent space exploration. According to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, the last meeting ran this year from Jan. 29 to Feb. 9. “There is a group called For All Mankind,” Elvis added, “which is trying to protect landing sites and other historical sites on the moon.” There’s also the very interesting fact that, in 2022, Canada extended its criminal law jurisdiction to the moon.

Yet, with the success of Odysseus, we now know that both space agencies and non-space agencies can start populating the moon with various things they wish to send up there. Private companies may have their own set of criteria for stuff they’re willing to blast toward the moon (Intuitive Machines requires that you fill out a form, for instance), but I suppose that’d be up to each company’s discretion. Might this be the push that was needed to get some lunar laws (like, real laws) etched into something more solid?

In fact, the biggest reason Odysseus is on the moon right now is thanks to NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, or CLPS. The agency basically created this program because it wanted a way to enlist private companies to take care of transit to the moon (aka, make the rocket and lander) so that its science experiments can just be the passengers. And even if NASA gets to reserve a few first class spots on the trip, other people can pay to have their science equipment onboard as well — and it doesn’t even need to be science equipment.

Source: https://www.space.com/lunar-policy-ethics-intuitive-machines-telescopes-moon-odysseus-lander