While sitting in his office, Naman Bajaj stared at the precious data that led to the final installment of his trio of published papers, each of which incrementally answers a very loaded question: Why do some planet-forming disks creep onto their own stars? The three studies were robust, interesting and most importantly, finished. But before closing the door on these last few data points, delivered by the famous James Webb Space Telescope, Bajaj decided to wring them for all they were worth. He certainly didn’t expect, however, to open yet another door.

“My advisor was gone for a conference or something for a month; I was just playing with the data and saying, ‘What more I can do? Is there anything more that this data can tell us?'” Bajaj, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, told Space.com.

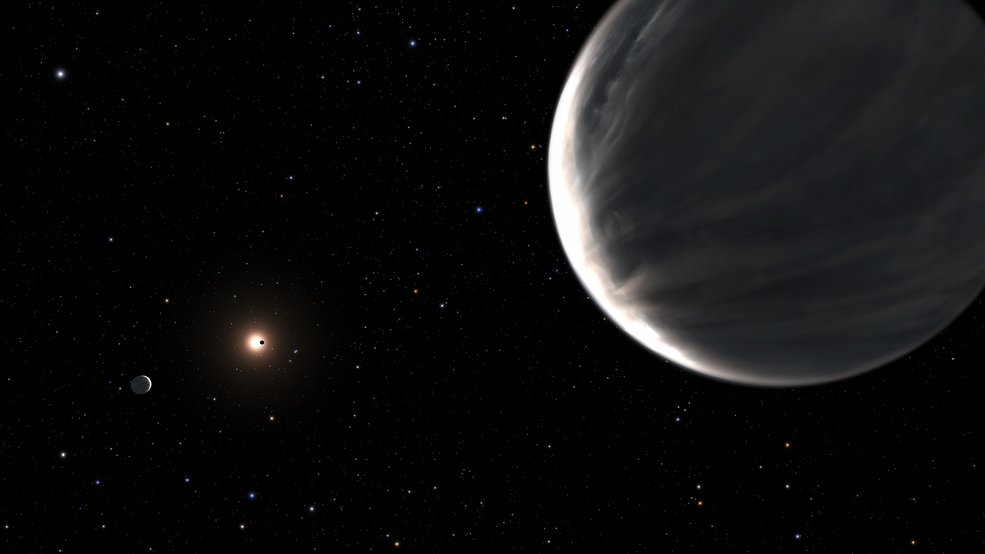

Soon, he would make a brilliant find. One of the star subjects he and his collaborators already spent so much time with was actually a double; it’s just that no one had noticed. The cosmos, we’re constantly reminded, is big enough that something as incomprehensibly huge as a pair of stars waltzing around one another can be missed. “One pixel in this image that we are looking at is 14 AU,” Bajaj said. For context, a single AU, or “astronomical unit,” represents the mind-blowing distance between our planet and the sun about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers). In a way, it is remarkable that a human can make this discovery at all.

To understand how Bajaj arrived at his conclusion, recall those first three papers. All three concerned the dynamics of matter-filled disks around stars. It is within these disks that planets can blossom from rocky or gassy seeds, which is why they’re so interesting to scientists. More specifically, Bajaj and his team were scratching their heads about how material from those disks can sometimes fall onto the stars anchoring them. It is something of a mystery why this happens.

“For example,” Bajaj said, “The Earth is going around the sun, but it’s not falling onto the sun because it’s constantly going around in that orbit.” According to the laws of physics laid out by Isaac Newton, if the orbit of an object isn’t interrupted, it shouldn’t just start changing its trajectory. So, the team reasoned, maybe something is disturbing such inward-falling disks and they’re not acting on their own. It would all make sense if the disks lost some angular momentum, for instance — but to do that, they’d perhaps need to lose some of their masses. So, how would that mass loss happen?

This is the basic question Bajaj and fellow researchers set out to answer.

In a nutshell, the team’s first paper confirmed that strong “winds” could be moving material from the disk vertically upward. The second paper was meant to calculate how much material zooms away through jets shooting out from the disks, which are similar to the winds but far faster and narrower. The third paper, meanwhile, was pretty much meant to connect the first two, comparing mass loss through winds with mass loss through jets. But Bajaj saw something fishy in his final dataset.

Source:https://www.space.com/space-exploration/james-webb-space-telescope/how-an-astronomer-accidentally-found-a-star-stuck-in-a-cosmic-waltz