The observatory’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) provides a different view of the famous pillars, revealing young stars that have not yet cast off their dusty “cloaks.”

This is not an ethereal landscape of time-forgotten tombs. Nor are these soot-tinged fingers reaching out. These pillars, flush with gas and dust, enshroud stars that are slowly forming over many millennia. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has snapped this eerie, extremely dusty view of the Pillars of Creation in mid-infrared light – showing us a new view of a familiar landscape.

Why does mid-infrared light set such a somber, chilling mood in Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) image? Interstellar dust cloaks the scene. And while mid-infrared light specializes in detailing where dust is, the stars aren’t bright enough at these wavelengths to appear. Instead, these looming, leaden-hued pillars of gas and dust gleam at their edges, hinting at the activity within.

Thousands and thousands of stars have formed in this region. This is made plain when examining Webb’s recent Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) image. In MIRI’s view, the majority of the stars appear missing. Why? Many newly formed stars are no longer surrounded by enough dust to be detected in mid-infrared light. Instead, MIRI observes young stars that have not yet cast off their dusty “cloaks.” These are the crimson orbs toward the fringes of the pillars. In contrast, the blue stars that dot the scene are aging, which means they have shed most of their layers of gas and dust.

Mid-infrared light excels at observing gas and dust in extreme detail. This is also unmistakable throughout the background. The densest areas of dust are the darkest shades of gray. The red region toward the top, which forms an uncanny V, like an owl with outstretched wings, is where the dust is diffuse and cooler. Notice that no background galaxies make an appearance – the interstellar medium in the densest part of the Milky Way’s disk is too swollen with gas and dust to allow their distant light to penetrate.

How vast is this landscape? Trace the topmost pillar, landing on the bright red star jutting out of its lower edge like a broomstick. This star and its dusty shroud are larger than the size of our entire solar system.

This scene was first captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope in 1995 and revisited in 2014, but many other observatories, like NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, have also gazed deeply at the Pillars of Creation. With every observation, astronomers gain new information, and through their ongoing research build a deeper understanding of this star-forming region. Each wavelength of light and advanced instrument delivers far more precise counts of the gas, dust, and stars, which inform researchers’ models of how stars form. As a result of the new MIRI image, astronomers now have higher-resolution data in mid-infrared light than ever before, and will analyze its far more precise dust measurements to create a more complete 3D landscape of this distant region.

The Pillars of Creation is set within the vast Eagle Nebula, which lies 6,500 light-years away.

More About the Mission

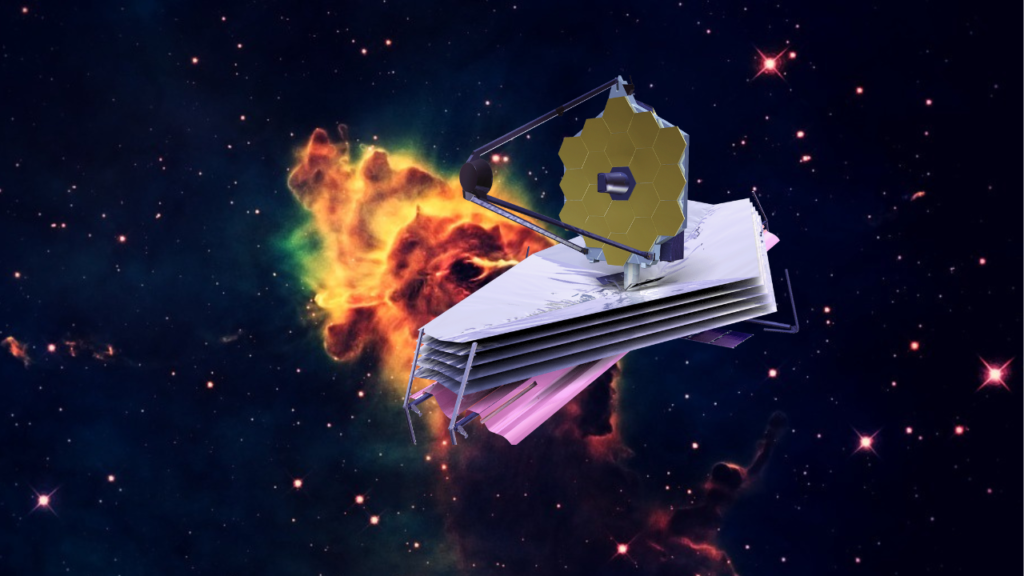

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).

MIRI was developed through a 50-50 partnership between NASA and ESA. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory led the U.S. efforts for MIRI, and a multinational consortium of European astronomical institutes contributed for ESA. George Rieke with the University of Arizona is the MIRI U.S. science team lead. Gillian Wright with the UK Astronomy Technology Centre is the MIRI European principal investigator. Alistair Glasse with UK ATC is the MIRI instrument scientist, and Michael Ressler is the U.S. project scientist at JPL. Laszlo Tamas with UK ATC manages the European Consortium. The MIRI cryocooler development was led and managed by JPL, in collaboration with NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach, California. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.