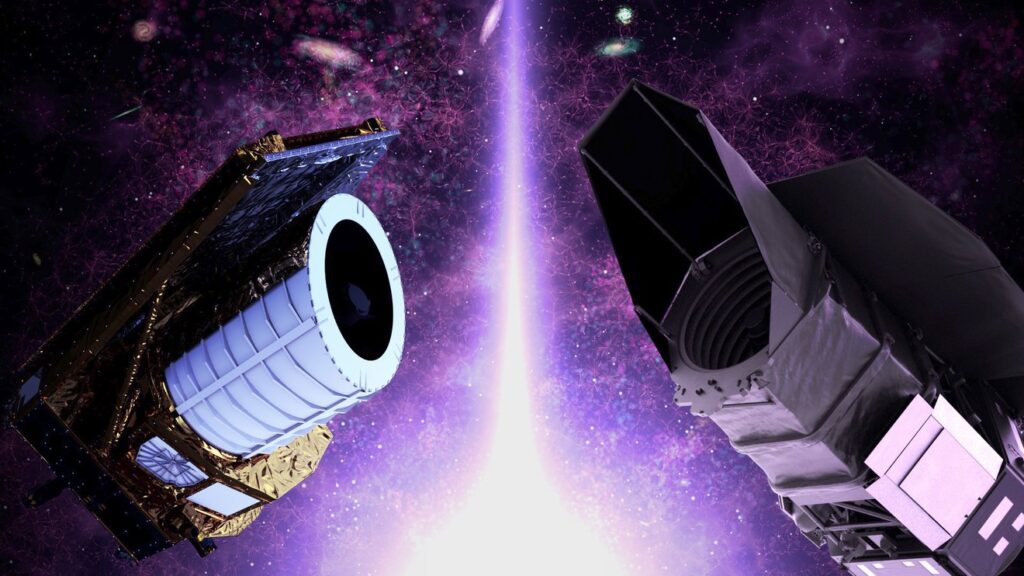

The two missions will study this as-yet-unexplained phenomenon in complementary ways.

A new space telescope named Euclid, an ESA (European Space Agency) mission with important contributions from NASA, is set to launch in July to explore why the universe’s expansion is speeding up. Scientists call the unknown cause of this cosmic acceleration “dark energy.” By May 2027, NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will join Euclid to explore this puzzle in ways that have never been possible before.

“Twenty-five years after its discovery, the universe’s accelerated expansion remains one of the most pressing mysteries in astrophysics,” said Jason Rhodes, a senior research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. Rhodes is a deputy project scientist for Roman and the U.S. science lead for Euclid. “With these upcoming telescopes, we will measure dark energy in different ways and with far more precision than previously achievable, opening up a new era of exploration into this mystery.”

Scientists are unsure whether the universe’s accelerated expansion is caused by an additional energy component or whether it signals that our understanding of gravity needs to be changed in some way. Astronomers will use Roman and Euclid to test both theories at the same time, and scientists expect both missions to uncover important information about the underlying workings of the universe.

Euclid and Roman are both designed to study cosmic acceleration, but using different and complementary strategies. Both missions will make 3D maps of the universe to answer fundamental questions about the history and structure of the universe. Together, they will be much more powerful than either individually.

Euclid will observe a far larger area of the sky – approximately 15,000 square degrees, or about a third of the sky – in both infrared and optical wavelengths of light, but with less detail than Roman. It will peer back 10 billion years to when the universe was about 3 billion years old.

Roman’s largest core survey will be capable of probing the universe to a much greater depth and precision, but over a smaller area – about 2,000 square degrees, or one-twentieth of the sky. Its infrared vision will unveil the cosmos when it was 2 billion years old, revealing a larger number of fainter galaxies. While Euclid will focus on cosmology exclusively, Roman will also survey nearby galaxies, find and investigate planets throughout our galaxy, study objects in the outskirts of our solar system, and much more.

The Dark Energy Hunt

The universe has been expanding ever since its birth – a fact discovered by Belgian astronomer Georges Lemaître in 1927 and Edwin Hubble in 1929. But scientists expected the gravity of the universe’s matter to gradually slow that expansion. In the 1990s, by looking at a particular kind of supernova, scientists discovered that about 6 billion years ago, dark energy began ramping up its influence on the universe, and no one knows how or why. The fact that it’s speeding up means that our picture of the cosmos is missing something fundamental.

Roman and Euclid will provide separate streams of compelling new data to fill in gaps in our understanding. They’ll attempt to pin down cosmic acceleration’s cause in a few different ways.

First, both Roman and Euclid will study the accumulation of matter using a technique called weak gravitational lensing. This light-bending phenomenon occurs because anything with mass warps the fabric of space-time; the bigger the mass, the greater the warp. Images of a distant source produced by light moving through these warps look distorted, too. When those nearer “lensing” objects are massive galaxies or galaxy clusters, background sources can appear smeared or form multiple images.

Less concentrated mass, like clumps of dark matter, can create more subtle effects. By studying these smaller distortions, Roman and Euclid will each create a 3D dark matter map. That will offer clues about cosmic acceleration because the gravitational attraction of dark matter, acting like a cosmic glue that holds together galaxies and galaxy clusters, counters the universe’s expansion. Tallying up the universe’s dark matter across cosmic time will help scientists better understand the push-and-pull feeding into cosmic acceleration.

The two missions will also study the way galaxies clustered together in different cosmic eras. Scientists have detected a pattern in the way galaxies congregate from measurements of the nearby universe. For any galaxy today, we are about twice as likely to find another galaxy about 500 million light-years away than a little nearer or farther.

This distance has grown over time due to the expansion of space. By looking farther out into the universe, to earlier cosmic times, astronomers can study the preferred distance between galaxies in different eras. Seeing how it has changed will reveal the expansion history of the universe. Seeing how galaxy clustering varies over time will also enable an accurate test of gravity. This will help astronomers differentiate between an unknown energy component and various modified gravity theories as explanations for cosmic acceleration.

Roman will conduct an additional survey to discover many distant type Ia supernovae – a special type of exploding star. These explosions peak at a similar intrinsic brightness. Because of this, astronomers can determine how far away the supernovae are by simply measuring how bright they appear.

Astronomers will use Roman to study the light of these supernovae to find out how quickly they appear to be moving away from us. By comparing how fast they’re receding at different distances, scientists will trace cosmic expansion over time. This will help us better understand whether and how dark energy has changed throughout the history of the universe.

A Powerful Pair

The two missions’ surveys will overlap, with Euclid likely observing the whole area Roman will scan. That means scientists will be able to use Roman’s more sensitive and precise data to apply corrections to Euclid’s, and extend the corrections over Euclid’s much larger area.

“Euclid’s first look at the broad region of sky it will survey will inform the science, analysis, and survey approach for Roman’s deeper dive,” said Mike Seiffert, project scientist for the NASA contribution to Euclid at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“Together, Euclid and Roman will add up to much more than the sum of their parts,” said Yun Wang, a senior research scientist at Caltech/IPAC in Pasadena, California, who has led galaxy clustering science groups for both Euclid and Roman. “Combining their observations will give astronomers a better sense of what’s actually going on in the universe.”

More About the Missions

Three NASA-supported science groups are contributing to the Euclid mission. In addition to designing and fabricating Euclid’s Near Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP) instrument sensor-chip electronics, JPL led the procurement and delivery of the NISP detectors. Those detectors were tested at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. The Euclid NASA Science Center at IPAC (ENSCI), at Caltech, will support U.S.-based investigations using Euclid data.